Shropshire Local Nature Recovery Strategy

Priority Bird Species

Introduction

The government has set legally binding targets to:

- Halt the decline in species abundance by the end of 2030

- Increase species abundance by the end of 2042 so that is greater than in 2022 and at least 10% greater than in 2030

- Reduce the risk of species’ extinction by 2042, when compared to the risk of species’ extinction in 2022

A Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) is intended to be a critical new tool for driving the national ambition to increase species abundance and reduce risk of species extinctions. Nationally, there will be 48 LNRSs, including one for Shropshire (including Telford and Wrekin).

The LNRS will describe opportunities, set priorities, and propose potential measures for the recovery and enhancement of species. It is being prepared by a Steering Group chaired by Natural England, and co-ordinated by Shropshire Council (the “Responsible Authority”), and including representatives of seven other organisations, including Telford and Wrekin Council.

Species Recovery within Local Nature Recovery Strategies: Advice for Responsible Authorities (Version 1: August 2023) has been issued by Natural England. It sets out an approach to help responsible authorities (RAs) achieve this goal in a consistent way. The approach involves two broad stages: identifying threatened and other locally significant species relevant to the strategy area (the “Long List”), and determining which of these species should be prioritised for recovery action (the “Short List”).

Species to be considered for inclusion in the Long List are

- Any native species which have been assessed as “Red List: Threatened” against International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) criteria (see https://www.iucnredlist.org/)

- Other native species that have been identified as “Threatened” by local Conservation Organisations

A draft paper, “Shropshire Local Nature Recovery Strategy: Priority Bird Species (v2)” was sent for comment to Community Wildlife Groups and stakeholders (Shropshire Ornithological Society (SOS) and Royal Society Protection of Birds (RSPB)) in September 2024, and an updated version incorporating the comments received, and initial proposals for the shortlist (v4), was distributed with a further request for comments.

The revised paper that follows (v5) incorporates comments received by the deadline of 31 December 2024. It is the final stage in producing the “Long List” of Bird Species, and incorporates the proposed “Short List”.

A section has been added, of recommendations to the Shropshire LNRS Steering Group, primarily to encourage joint action by all LNRSs to encourage Government to facilitate implementation of LNRS across the whole country through the planning system, and local authority actions.

Priority Bird Species

The UK was home to 73 million fewer birds in 2023 than it was in 1970, according to research from the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO). This staggering number – a decline of almost a third – is almost impossible to comprehend, but it indicates the scale of the challenge for LNRSs.

Table 1 (attached as Appendix 1) includes all the native bird species which have declined substantially, which occur in Shropshire, and have been

(1) Red listed by IUCN, in categories CR (Critically endangered), EN (Endangered), VU (Vulnerable) or NT (Near threatened)

(2) Listed as species of principal importance in England under Section 41 of the Natural Environment and Rural Communities (NERC) Act 2006. Some wild birds are listed as rare and most threatened species under this Act, and local Planning Authorities must have regard for their conservation as part of planning decisions. Restoring the populations of the S41 species are the Government’s biodiversity targets, enshrined in international treaties.

(3) Included in the Red and Amber Lists of Breeding Birds of Conservation Concern in Shropshire, published by SOS in 2020. The lists highlight those native species that are under greatest threat in the County. It is based on local data and observations collected over the last 35 years, culminating in the publication of The Birds of Shropshire by Liverpool University Press in 2019. The approach largely follows that used to produce the national lists published in Birds of Conservation Concern 4 in 2015. The County and national lists are complementary, and both will be used to determine local conservation priorities. Three main criteria have been used to select the species listed:

-

- Disappearance from large parts of the County (from more than 50% of the survey squares they occupied in 1985-90, to qualify for the Red list, and from more than 25% for the Amber list)

- Big reductions in the County population (by more than 50% to qualify for the Red list, and 25% for the Amber list, over the same period)

- The population is vulnerable, because it only breeds at a few sites.

A detailed explanation of the criteria, how they have been applied, and supporting references, can be found in a paper in the Shropshire Bird Report 2019.

(4) . Listed in the Shropshire Biodiversity Action Plan (SBAP), launched in 2002. Some species had their own Action Plan (shown as “Species AP” in Table 1), but others were listed under the Farmland Birds Action Plan (shown as “Farmland AP” in Table 1. The Action Plans are now out of date, but can still be found on the Shropshire Council website. These species had already declined substantially by 1990 (before the baseline year for the SOS Red and Amber Lists, so they did not qualify for inclusion on those lists, but must be included in the LNRS.

(5) Included amongst the 12 Species Action Plans, including four bird species, Dipper, Snipe, Tree Pipit and Willow Tit, published by the Stepping Stones project (see https://middlemarchescommunitylandtrust.org.uk/info-sheets/ Stepping Stones is a nature conservation programme covering over 200km² in the Shropshire Hills. It is creating more bigger and better spaces for wildlife, and linking them with wildlife ‘corridors’. The project is led by the National Trust but involves a number of partners, including The Wildlife Trusts, Natural England and Shropshire Hills National Landscape.

(6)Surveyed by Community Wildlife Groups. The first group, the Upper Onny, started to survey disappearing Lapwing, Curlew and Skylark in 2004, and the network of 10 groups was complete by 2018 (see https://www.shropscwgs.org.uk/). All groups monitor Lapwing and Curlew. The Other Target Species were revised in 2024, and there are now five main target species (MT), Cuckoo, Kestrel and Red Kite, in addition to Lapwing and Curlew, and a list of other target species (OT), which are now no longer included in CWG Annual Reports. Members are now encouraged to submit records of these species, and any others seen on surveys, to BTO BirdTrack.

(7) Identified as Regional priorities for RSPB, as Woodland specialists (W), Breeding waders (BW) or Species associated with Urban environments (U).

Table 1 then includes the Status and Abundance of these species in 2014, taken from The Birds of Shropshire, using Status and Abundance Definitions set out in Appendix 2, together with the population estimate at that time; the national Red, Amber and Green list status defined in The status of our bird populations:BoCC5 and IUCN2 (Stanbury et al 2021); the BTO National Breeding Population Estimate (UK 2016 Pairs unless otherwise stated); the proportion of the UK breeding population which breeds in Shropshire, whether the species population in Shropshire is nationally or regionally important (including RSPB priorities as Woodland specialists (W), Breeding waders (BW) or Species associated with urban environments (U)); and whether there is hard evidence for a change in status, in the period 2015-2023

Priority has been given to species that currently breed in the County, set out in Section 1, as these must be the species that can be most effectively helped by the LNRS. Section 2 lists species that no longer breed here, although they have been listed by IUCN or S.41, and Section 3 includes all species that occur in the County, and are on the IUCN Red list, but which are only Passage Migrants or Winter Visitors (or both), and Vagrants. Although there may be few specific actions that can be undertaken in the County that will contribute to the recovery of these non-breeding species, a general improvement in habitats overall will mean they are in a better condition when they return to their breeding grounds. Reducing disturbance of the large Black-headed Gull roost at Ellesmere, which are mostly winter visitors, not birds that breed in Shropshire, is the only proposed action to directly help wintering species.

Table 1 (Section 1. Breeding) lists species in alphabetical order of their common name, then whether it is proposed that they are included on the LNRS Long List (all except four of the listed species). Section 2. Species no longer breeding and Section 3. Passage Migrants and Winter Visitors on the IUCN List that Occur in Shropshire both list species that are not recommended for inclusion in the LNRS Long List.

Shropshire Ornithological Society (SOS), the pre-eminent bird conservation organisation in the County since 1955, and the Royal Society of the Protection of Birds (RSPB), both support the approach adopted in this paper, to prioritise the species on the SOS Red and Amber Lists of Breeding Birds of Conservation Concern in Shropshire, based on analysis of the species accounts and other data in The Birds of Shropshire, published by Liverpool University Press in 2019.

Additions to the Birds of Conservation Concern in Shropshire

Firstly, the national BTO/RSPB/JNCC Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) started in 1994. BTO can produce statistically valid population trends at County level for species that are recorded on an average of at least 30 squares per year. There are Shropshire BBS trend graphs for 34 of the most common species, including 11 of the threated species listed in Table 1. These trend graphs and percentage change figures for the County have been recalculated, starting with a baseline of 1997, since when more than 50 squares have been surveyed each year (there were less than 20 squares surveyed in the years 1994-96, making the baseline index unrepresentative). The results have led to some changes in the priority species in Table 1. In particular, it has allowed a review of the SOS Red and Amber lists, and House Martin, Swallow and Collared Dove have been added to the Amber list for the first time. The support of the BTO in helping facilitate the LNRS in this way is gratefully acknowledged.

Secondly, local monitoring has identified three species that should be added to the County Red List

- Red Grouse, which has declined by more than 50% since 2018, probably mainly due to habitat loss (heather beetle and encroachment of bracken, and bad weather affecting productivity in several breeding seasons). The LNRS must include a habitat management plan for heathland management and restoration.

- Firecrest, which has become established as a regular breeding species over the last 10 years. That should benefit from improved woodland management, and does not require any additional measures.

- Herring Gull, which has recently become established, nesting on rooftops in Shrewsbury, together with Lesser Black-backed Gulls.

A Farmland Bird Index for Shropshire

There are a number of farmland species that are in decline, but which do not occur in sufficient BBS survey squares to produce a statistically valid trend graph As indicated above, four are farmland seed eating birds that were identified as priorities in the SBAP, drawn up in 2002. These species (Corn Bunting, Linnet, Reed Bunting, and Tree Sparrow) are on the national Red List (BoCC5), but are not all on the County Red List because their decline mainly occurred before our baseline year of 1990.

There are then five other species (Grey Partridge, Kestrel, Lapwing, Turtle Dove and Yellow Wagtail) that are on the National Farmland Bird Index (NFBI) and on County Red or Amber lists (BBoCCS) that are not individually found in sufficient squares to generate a BBS trend.

BTO considers that it would be possible to produce a statistically valid trend graph for some or all of these species – a Farmland Bird Index for Shropshire. This would facilitate monitoring the population trend for farmland birds, a key requirement for the implementation of the LNRS, and most of the others. However, BTO do not have the resources to produce such an index at present and the Shropshire LNRS team should raise this will colleagues across the country to help BTO make the case to JNCC and Defra for increased resources to do this work.

The LNRS Long List

During the consultation, only one additional species was proposed for inclusion in the Long List, Redstart. It is on the national Amber List, and the Shropshire population is regionally important. There is no hard evidence of population change in the County, but it declined by 12% in England, and 30% in Wales, over the 10-year period 2012-22. It has been added to the Long List.

Two species have been removed from earlier drafts of Table1. Section 1, Hawfinch and Turtle Dove, as they no longer breed here. They are included in Section 2. Species No Longer Breeding.

It was suggested that Red Kite be retained on the Long List, in spite of its rapid population increase, because it is charismatic and popular, and will therefore help with the promotion of the LNRS. As only endangered species are included on the Long List the LNRS Steering Group decided that Kite should not be included.

Otherwise the list of species in Table 1 is unchanged from the version sent out for consultation.

The LNRS Short List, and Strategy for Recovery

When the County LNRS “Long List” was finalised, as set out in the revised Table 1, a “Short List” was drawn up and included in the revised draft of the paper circulated for consultation in December 2024.

These are species on the Long List that need specific programmes of conservation, because they will not benefit sufficiently from generalised improvements to habitats. These species are:

- Curlew

- Dipper*

- Pied Flycatcher

- Snipe*

- Swift

- Tree Pipit*

- Wheatear

- Whinchat

- Willow Tit*

Species marked with an asterisk (*) have Species Recovery Action Plans produced by the Stepping Stones project.

During the consultation period it became clear from annual counts on Long Mynd and Stiperstones that Red Grouse had declined by over 50% since 2018, so it was added to the Red List of Breeding Birds of Conservation Concern in Shropshire by SOS, and to the Short List in the LNRS.

Nightjar was added to the Short List following consultation on the draft with Natural England, Forestry Commission and Environment Agency.

Lesser Black-backed Gull was added because of the need to limit disturbance at the nationally-important winter roost site at Ellesmere. It is the only species listed because of threats to its population in winter.

Short-listed species in the draft strategy published for consultation in August 2025 are therefore

Curlew Pied Flycatcher Wheatear

Dipper Red Grouse Willow Tit

Nightjar Swift Lesser Black-backed Gull

The other recommended species for the Short List have not been included in the draft for consultation, but they are included in the appropriate Assemblages

Snipe Tree Pipit Whinchat

These 12 candidate species for the Shortlist are highlighted Yellow in Table 1, Section A, column T (August 2025)

Assemblages

Most species on the Long List will benefit from a sustained programme of farmland improvement, targeted at improving wildlife habitats rather than agricultural output. Others will benefit from changes to woodland management. Similar “assemblages” will benefit from other improvements in specific habitats, as set out below.

The specific habitats, and species that would become less threatened as a result of the proposed improvements to them, are also shown in Table 1, and discussed below.

i. Farmland

Farming dominates land use in the County, taking up over 80% of the land, and many of the threatened species have been reduced by agricultural intensification since the early 1970s. The greatest potential for species recovery lies in making farmland a less hostile environment.

Although the habitat of each of the Red and Amber List species listed as benefiting from a Farmland Bird Assemblage Recovery Plan are different, they would all benefit to a greater or lesser extent from

- Planting more hedgerows, and increasing the width, height and species diversity of those that remain.

- Planting native trees in the hedgerows, to improve their function as wildlife corridors for woodland species.

- Creating ponds, scrapes and boggy areas, particularly on low-lying ground

Rn arable land, far more biodiversity, including priority bird species, would be provided by:-

- Increasing the size and plant diversity of field margins, which should not be used as tracks by farm vehicles. They should be allowed to grow wild, to provide habitat for voles and mice, providing food for Barn Owl and Kestrel. Seeds from plants in the margins will increase the food supply for birds, and they will also provide invertebrate food.

- Reduction of use of herbicides and pesticides. Many species will have any increase in food supplying, including those dependent on “aerial plankton”: Swift, Swallow and House Martin.

- Reduction of use of inorganic fertilisers (and replacing them with natural ones instead, if necessary), and the adoption of best-practice cultivation to help improve soil health and increase the numbers of invertebrates.

- Increasing the proportion of spring barley, and over-winter stubbles, will directly benefit several species, specifically Lapwing, still in catastrophic decline, and Corn Bunting, which is regionally important. The winter “hunger gap” of the seed eating birds will be reduced.

- Reverting silage crops to single late cut hay meadows.

- Including a ‘Set-aside’ option in agri-environment schemes: A previous version of set-aside paid farmers to take a proportion of arable land out of production. operated until 2007. The BBS graphs for several species show this period as a population high point, followed by a steep decline, and a new set-aside scheme would be a valuable land-management option to support many farmland species.

On pasture land, sheep and cattle stocking levels should be reduced, to allow the regeneration of diverse swards with more invertebrates and plants.

Wormers passing through sheep and cattle (anthelmintics, particularly ivermectins) ensure that chemicals designed to kill invertebrates are deposited on the land in large quantities. Dung beetles have largely disappeared as a result, but less conspicuous invertebrates will have been equally reduced.

To meet the Government’s 30×30 target (In 2020, the government committed to protecting 30% of the UK’s land for biodiversity by 2030), consideration should be given to introducing set-aside and / or low intensity grazing for non-arable land. This protection is likely to be focussed on Protected Landscapes, but this would only relate to less than half the County, so similar action should be considered for all farmland

ii. Woodland

Shropshire is well wooded, with 8.5% of the land covered by woods of at least 0.1 ha in 2014 (58% broadleaved, 29% conifer, 9% mixed, 3% miscellaneous). Forestry Commission owns 16%, and the other 84% is in different, mainly private, ownership.

Several species, identified in Table 1, would benefit from targeted improvements to woodland. These species generally occupy different habitat niches, and need different actions to improve those habitats.

- Most of the species on the Long List are in decline because of a loss of invertebrate food, so specific actions are needed to increase that (including over woodland, as well as in it).

- Rewetting the woodland floor (including blocking drains and putting “leaky dams” in small watercourses) is necessary for Willow Tit and Woodcock, and would help most other species as well, as wet ground usually supports a higher density of invertebrates.

- Woodlands along the banks of rivers and streams should be managed to increase the supply of invertebrates for Pied Flycatcher (regionally important in Shropshire).

- Targeted removal of scrub (understorey) in deciduous woods on steep slopes would help Wood Warbler (also regionally important in Shropshire).

- Opening up plantations planted on heathland and heather moorland would increase habitat for Nightjar

- Lesser Spotted Woodpecker has probably suffered the most catastrophic decline of all, and they only nest in dead trees or dead branches on living trees. An increase in the volume of deadwood is essential, but also action to stop the tendency to tidy up, which usually involves removing dead wood.

- Scattered trees on clearfell is ideal habitat for Tree Pipit, which will also benefit from “edge management”, if that means a few scattered trees on the edge of woodland.

- Funding will be scarce, so action to Promote the use of woodland funding opportunities should be much more explicit, targeted at the Nature Recovery priorities, and will not be used for planting on the habitats of priority species of bird or other taxa, or for planting coniferous (or any other) monocultures.

- Improved monitoring and management is essential to ensure all priority species start to increase, as a result of habitat improvements

Many of the forestry plantations are on heathland and heather moorland, which, as a result, are much rarer habitats now. Restoration of these habitats should be promoted by removing the trees altogether where appropriate, particularly where that would increase the size of existing heathland e.g. on and around Long Mynd and Stiperstones.

iii. Rivers, Other Watercourse and Waterbodies

Diffuse pollution, particularly run-off from agricultural land, should be reduced by improved land management and appropriate siting crops.. This would increase the numbers of fish and larvae, and benefit several species of water-bird, including Kingfisher. It would also increase invertebrates near the rivers, benefiting Grey Wagtail and Pied Flycatcher.

Sewage treatment works need to be appropriate for the community they are serving, although this doesn’t reduce the nutrient loading of their discharges, and storm sewer overflows need to be eliminated. As well as insects and fish benefitting so will aquatic macrophytes which are important for both the other two.

Flash flooding is a threat to Dipper (reduced feeding opportunities), and birds that nest on shingle in the river bed, such as Common Sandpiper. “Slow the flow” measures should be introduced e.g. grip blocking on moorland, removing inappropriate drainage systems, use of log dams and riparian woodland, Such measures would also reduce downstream flooding.

iv. Rewetting, particularly peatland, and Rush Management

Farmland has been systematically drained over many centuries, but particularly from the 1970s onwards, which has contributed to the decline of several species listed in Table 1. A programme of blocking drains and drainage channels, and removing excess rushes, would complement the actions listed in iii) above, and benefit Curlew, Snipe and Reed Bunting, among other species. Some low-lying pasture fields also have potential for rewetting, particularly if wetland plant communities can become established.

v. Heathland and Moorland Restoration

Whinchat is on the SOS Red List, and the recent decline in the Red Grouse population has resulted in it being added to the Red List. Long Mynd is the only site where Whinchat now breed regularly, and it holds the large majority of the Red Grouse population (the only other, smaller, population in Shropshire is on The Stiperstones). Whinchat nest primarily in bilberry heath mosaic, and Grouse are totally dependent on heather.

The Long Mynd is only one of two SSSIs in the County designated for its birds (the Upland Bird Assemblage), but it no longer meets the SSSI qualification criteria. The most recent condition assessments of the various sections of the SSSI, mainly more than 10 years ago, concluded it was “Unfavourable – Recovering”. Natural England are due to undertake a new condition assessment of the SSSI in the next year or so, but it is not clear yet whether it will recommend, or insist on, habitat and other improvements to ensure the recovery of these two species, and the other declining species in the Upland Bird assemblage. The National Trust, as landowner, must be encouraged to improve the area and quality of heathland for Red Grouse, and bilberry heath mosaic for Whinchat, through its Long Mynd Conservation Plan.

Elsewhere, at lowland heathland such as that at Prees Heath, management will be required to control native and non-native invasive species, and to remove plantations on former heathland and moorland sites where there is a reasonable prospect of restoration.

vi. Scrub/heath mosaic (ffridd)

These are the areas between the enclosed more intensively managed lower fields and the unenclosed hill and moorland, diverse habitats including some or all of the following; scattered trees and small woodlands, bracken, heather and bilberry heath, wet and dry unimproved grassland, bog, scree and rock. It is a particularly important and vulnerable habitat in the Shropshire Hills, but it has benefitted very little from conservation action to date. Bracken is an important part of the habitat, but each site needs to be assessed to consider if it is becoming too dominant. Stocking levels also need to be considered – if levels are too high it becomes grassland and too low it becomes woodland.

Many of the Long List species (including nine on the SOS Red List, and three on the Amber List) rely upon it, and it has only survived up to now because it is usually on steep slopes that are difficult to ‘improve’ for agriculture. These areas would benefit from both heathland creation and rewetting. It is likely however that these ffridd areas will now be targeted for tree planting for carbon/monetary reasons, with consequent losses of key species. These threats to this habitat should be resisted through LNRS.

vii. Nitrogen Deposition

Deposition of nitrogen from the atmosphere is a threat to many important habitats, including some of those mentioned above. particularly heathland, moorland, and ffridd, It is consequently impacting on invertebrate populations, particularly butterflies, and therefore indirectly contributes to the reduction in bird populations. Efforts should therefore be made to ensure an overall reduction in atmospheric nitrogen, and specific sources such as chicken sheds should be removed where they directly affect sensitive habitats.

viii. Houses, gardens and the Built Environment

Suburban gardens now support more birds than farmland, and an LNRS campaign to encourage householders to put up nest boxes, and feed the birds on the LNRS target list, will provide an opportunity to engage with local residents to “do their bit” to support the wider aims and targets of LNRS. However it is essential to maintain good hygiene around feeders to minimise disease.

More wildlife friendly planting should also be encouraged, leaving overwintering stems on plants (great seed for the finches and tits), leaving areas of garden more relaxed and natural, mulch beds with leaves (loads of bugs, etc will overwinter or be eaten by blackbirds, etc). Conifers should not be-devilled – goldcrest and finches love the seeds so we want to encourage home owners to allow them to fruit (but not get too tall so that they have to be felled). A wildlife friendly gardening campaign should be launched alongside the strategy. Shropshire Council should be advised to manage their estates in this way too, and Highways need to reduce or give up flailing hedgerows, especially during the breeding season. Much of it is unnecessary, and a budget saving that would be positively beneficial.

No cultivation or the application of pesticides or fertilisers should take place within a two-metre buffer strip next to a hedgerow, and cutting ban around the hedgerow from 1 March to 31 August (inclusive), was introduced on farmland. on 23 May 2024. LNRS should campaign for similar rules for all other hedgerows, particularly those adjacent to dwellings and highways.

Swifts mainly nest in the roof-space of older houses, and are a special case, in that they can be protected to some extent through the Planning system, if the buildings they inhabit are identified. House Martins, too, frequently have their nests deliberately destroyed by unsympathetic householders. The Planning Authorities (Shropshire, and Telford and Wrekin, Councils) should ensure that Planning Permissions for all new buildings and for renovations include Swift bricks and House Martin cups. Swift groups can provide information to help the Planning Authorities, but it is the responsibility of the Authorities to implement the policy, and they should be more rigorous in checking Swift Mapper each time a planning application is received to see if Swifts in particular are already breeding on that building. However, Swift groups don’t know all the sites and some towns and villages have not been surveyed, so it should be assumed that they are there, or could be there if breeding sites are available.

Swallow barns (a shed basically) should be erected where any farm building conversion takes place, to provide the Swallows with an alternative nesting site nearby. This requirement should become a mandatory part of the planning process.

Each Parish Council should be encouraged to actively support these parts of the LNRS in their own area, and monitor the populations of priority species.

ix. Reduce disturbance by humans

The British/NW European Lesser Black-backed Gull roost count threshold for international importance is 5500. At Ellesmere, counts have been over 8000 for at least the last three consecutive years in autumn, but roosting gulls are regularly disturbed by human activity – boats and paddle-boarders. A management plan for the Mere is needed to reduce the disturbance. Such a plan would also improve the habitat for breeding Great-crested Grebe.

Other important wildlife sites suffer from human disturbance, but numbers of tourists are increasing, and being actively encouraged. The LNRS should seek to get this danger recognised and mitigated in the Shropshire Destination Management Plan and the Shropshire Hills Sustainable Tourism Strategy and Action Plan.

The Special Case of Curlew

The Birds of Shropshire reported that, between 1990 and 2013, the County Curlew population declined by 77%, from an estimated 700 pairs to 160 pairs. Bird Atlas work in 2008-13 showed they had disappeared from 62% of tetrads where they had been found in the earlier 1985-90 bird Atlas. Continued population monitoring by 10 Community Wildlife Groups has shown a continuing decline of about 35% since 2013, and the county population is now down to an estimated 100 – 110 breeding pairs. At the current rate of decline, the County population will halve in 12 years, and be extinct in 24.

Curlew is “the most important bird conservation priority in the UK” (Brown et al, 2015) as we have a special responsibility because the UK breeding population is estimated at 28% of the European Population, and 18-27% of the World Population.

The Shropshire Curlew population is nationally and regionally important. There are an estimated 500 pairs of Curlew left in the south of England (south of a line from the Dee estuary to The Wash). The International Union for Nature Conservation (IUCN) criteria include maintaining the range of threatened species, as well as their populations. The Shropshire population is over 20% of that in southern England.

The Shropshire Ornithological Society Save our Curlews campaign has shown that predation of nests and chicks is now the main driving force of the decline. As ground-nesting birds, mainly in farmed grassland, Curlews are vulnerable to agricultural operations, but in practice they are predated before such operations can destroy nests or chicks. Therefore, habitat improvements (unless they include reducing the number of predators at the landscape scale) will not, in themselves, achieve a reversal of the Curlew decline. Reports showing the results of SOS project work can be found on the SOS website https://www.shropshirebirds.com/index/bird-conservation/save-our-curlews/

Curlew is on the Red List of Breeding Birds of Conservation Concern in Shropshire, but it is a special case, as habitat improvements will not help reverse the decline (although they will be needed, if predation pressure is reduced).

The increase in predator pressure in modern times is attributed to the 60 million gamebirds released into the British countryside each year, estimated at over 2,000,000 in Shropshire alone in 2018 alone. There is no evidence that predator control at a local or estate level is effective. It just creates a vacuum, and more predators move in to compete for the territory. If Curlew is to be saved from local extinction, efforts must be made through the LNRS to reduce gamebird release.

Recommendations to Shropshire LNRS Steering Group

-

Recommendations specific to Shropshire

The Steering Group should

- Work to ensure that professional advice is available to individual landowners and farmers on the effective implementation of land management change to facilitate LNRS objectives

- Several important wildlife sites suffer from human disturbance, but numbers of tourists are increasing, and being actively encouraged. The LNRS should seek to get this danger recognised and mitigated in the Shropshire Destination Management Plan and the Shropshire Hills Sustainable Tourism Strategy and Action Plan

-

Recommendations that apply to several or all LNRS in England

Several of the issues and concerns raised in this paper are not specific to Shropshire, but the desirable changes would be more effective and much easier to achieve if there was coordinated action with improved policies facilitated by Government action. Some examples are included in the recommendations below.

- Work with all LNRS across England to make the case to JNCC and Defra for increased resources for BTO to produce a Breeding Bird Survey index of population trends at the County level, to help all LNRS identify local priorities, and, in the longer term, to monitor the effectiveness of their strategies.

- Work with all LNRS across England to make the case to Defra to include the LNRS in the National Planning Policy Framework, so it is taken into account by all Planning Authorities when considering planning applications. This would benefit, in particular, species that nest in buildings, such as Swift, Swallow and House Martin.

- Work with relevant other LNRSs to seek inclusion of options to fund the control of bracken, and manage heathland and ffridd through agri-environment schemes

These issues should be taken up with the other LNRSs..

Conclusion

Readers should send and comments on this document by email to leo@leosmith.org.uk

More importantly, readers should also view the map & draft strategy document and submit feedback: www.shropshire.gov.uk/lnrs

References

The Birds of Shropshire (Smith 2019) Liverpool University Press

The status of our bird populations:BoCC5 and IUCN2 (Stanbury et al 2021) British Birds 114 December 2021 pp748-755

Breeding Birds of Conservation Concern in Shropshire (The Shropshire Bird Report 2019)

The Eurasian Curlew – the most pressing bird conservation priority in the UK? (Brown, D., et al. 2015) .Brit. Birds 108: 660–668.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Graham Walker, Chair of Shropshire Ornithological Society: John Martin, County Bird Recorder; John Arnfield, for publishing draft proposals for consultation on the SOS website (www.shropshirebirds.com): and members of the SOS Conservation Sub-committee, together with Mike Shurmer (RSPB Head of Species England) and Jamie Murphy (RSPB Senior Conservation Officer West Midlands), for information and advice on the species listed in Table 1; and James Heywood (the Breeding Bird Survey National Organiser at the British Trust for Ornithology).

Contributions on Swift were received from Carol Wood , current chair and leader of the Shropshire Swift Group, and former local Swift Champion, and Peta Sams, former holder of this position, and co-founder and administrator of the national Swifts Local Network working for swift conservation across the UK. ‘

Leo Smith

August 2025

Leo@leosmith.org.uk

Appendix 1. Table 1: Threatened Bird Species in Shropshire

See separate Spreadsheet (Table 1. Threatened Bird Species in Shropshire: The LNRS Bird Species List (August 2025)

Appendix 2. Status and Abundance Definitions in The Birds of Shropshire 2019

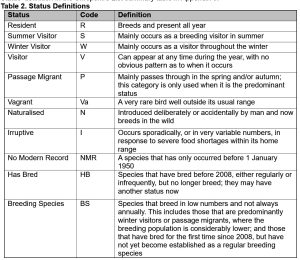

Each species has been allocated to at least one of the categories in Table 2. The table includes a code for each definition, which has been used as part of the ‘Shropshire Status’ definition in the Shropshire List summary table in Appendix 6.

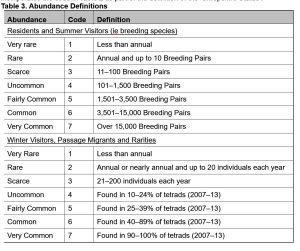

Each species has also been allocated an abundance score based on the definitions below.

‘Resident’ species may have seasonal, sometimes substantial, movements of individuals in and out of the County, and, particularly in the case of species that breed in the uplands, may occupy different areas and habitats in the winter. Many ‘Summer’ and ‘Winter Visitors’ pass through in larger numbers as they arrive or depart; in neither case do the status definitions cover these movements, and they usually refer to the predominant status unless there is a significant discrepancy between the two, in which case both are mentioned (e.g. a scarce summer visitor but common passage migrant). In other cases, the ‘Resident’ population is largely stable, but there is a significant influx of ‘Winter Visitors’, and they determine the primary status. Occasional ‘out of season’ records have been discounted, but may be referred to in the account. Some passage migrants are still present into the winter season, but have usually departed by mid-November, and others occasionally pass through during the winter period; in neither case are they considered to be winter visitors. Occasionally, some regular visitors are also irruptive and arrive in very large numbers. The ‘Has Bred’ category makes no distinction between previous occasional or regular breeding. Two species, Cormorant and Cetti’s Warbler, appear to be resident, but breeding has yet to be proven and they are defined as ‘Non-breeding Residents’.

The definitions in Table 2 have been used in conjunction with the status category to give some indication of the abundance of an individual species. Where a population is supplemented by releases this is also noted in the heading to the account, and denoted by the code ‘SR’ in the Shropshire List summary table in Appendix 6. This table also incorporates the code in Table 2 as part of the definition of the ‘Shropshire Status’.

Appendix 3. Table 4: Population trends since 2014